Special event: Double Exposure in Belle Park

Dorit Naaman

Driving into Kingston, Ontario, one might notice an unexpected sight: a Totem pole neglected and unmarked. Why is it here, and how did it get here? The pole marks the entrance to Belle Park, a recreational facility, which was built on a landfill. The landfill in turn was built on a wetland. And the wetland formed a rich habitat connecting Belle Island to the shore of the Great Cataraqui River. As a multilayered site marked by ongoing environmental and colonial violence, Belle Park is also a site of natural regeneration and the persistence of Indigenous communities. The site is currently an urban park, and a home to many of Kingston’s un-housed people.

In 2020, together with a historian and a Metis curator, we embarked on a collaborative Research-Creation project that includes geographers, environmentalists, artists, Indigenous community members and other park stakeholders. We aim to bring attention to this site through performances, audio and video documentaries, audio and physical walking tours, AR, maybe VR and more. The Belle Park Project seeks to illuminate the unseen, denied, generative, and unpredictable dimensions of this space, in order to imagine possible and less-toxic futures. In this presentation I will briefly discuss one artistic interventions in the park.

In this talk I will examine collaborative structures in the Belle Park Project to provide examples of productive collaborative artwork, as well as challenges and dead ends. I will discuss Indigenous principles of ethical collaboration (or working in a “good way”), and will situate our working process within both the socio-political context of Canada and of Research-Creation.

Keynote: Social Chemistry 101: Ethics and Actions

Since the turn of the 21st century, artistic projects that invite exchange, imagine new social relationships, and provoke individual and collective actions have grown increasingly influential, especially amongst a younger generation of creative practitioners eager to confront the unprecedented global challenges of our time. This collaborative, transdisciplinary approach is driven by the desire to connect, to look outside oneself in meaningful and tangible ways, and to positively impact daily life within specific communities. But to do this effectively, what kinds of creative processes and complex power relations must be attended to– or willingly upended– to co-create a compelling socially-engaged art project?

Above all, the messianic desire to “do good” as a primary motivator must be critically interrogated, both in the field and in the classroom. Social practice requires genuine exploration rather than aiming to prove established hypotheses. Re-learning from people with diverse forms of knowledge and life experiences, as well as unlearning one’s own conscious and unconscious habit patterns, often happens at a scale and pace that produces discomfort. What challenges arise when bravely refusing to pre-determine what “outcome” will result from a co-orchestrated exchange—or how “measurable” an impact it will have? What methods allow makers to cultivate a nuanced awareness of local histories and conventional polemics, while simultaneously encouraging more inventive poetics to emerge? In today’s talk, Matthews will discuss these complex artistic and pedagogical dynamics by examining recent projects, with an eye towards the ethics of cultural production in the public sphere.

Keynote: Decoloniality, The Evolving Critique on Practices of Power

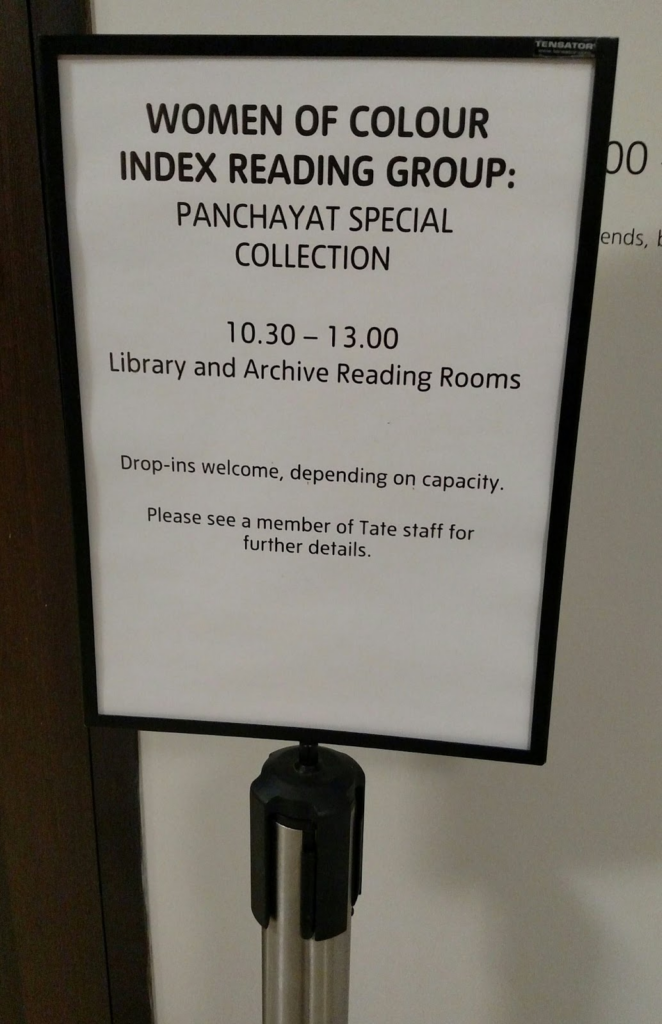

Image: Panchayat Special Collection at the Tate Library as part of the WOCI Reading Group close readings 29 Apr 2018

@WOCIReading

Friday‘s session w@TateResearch i#UnwrittenHistories #Panchayat- Collection #ArtEducation #DismantledCommunities #ArtInCommu- nity #CollectiveWorking

The keynote will address various aspects that relate differently to the symposium yet are connected to my own experience and biography. Naturally, as a person of colour, I am interested in the historical and current place of political, cultural, and social dynamics, historical inequalities and injustice and the way decisions are and have been made. Furthermore, I consider how normative forms, including the curriculum, are communicated and endorse collaboration both as a further form of inclusion and exclusion.

Here, the importance of archives and of special collections, both personal and institutional, have been evident in activating criticality or critical practice beyond the reach of a powerfully defended canon. What I mean by this is the only way to build bridges is through prolonged enquiries and altercations.

To address the important questions of our times, including the place and pace of transformative change, artists, researchers, and the curatorial praxis need to remain aware of the way in which such change is often partially observed or eclipsed and then quickly dismissed – especially in the way art and design environments usually ‘capture cultural democratic tendencies’ in the swings and roundabouts of academic discourse.

We need to remain vigilant and to evaluate the way artists lives, ideas, thoughts, and works can seem to play an important role for purposes that might remain superfluous or fashionable. How can critical practice be sustained? How do we remain steadfast and enabled to undo the harm that is present in places where culture is mediated formally and informally?